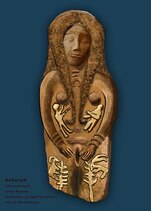

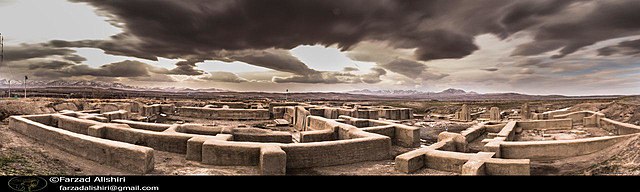

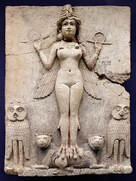

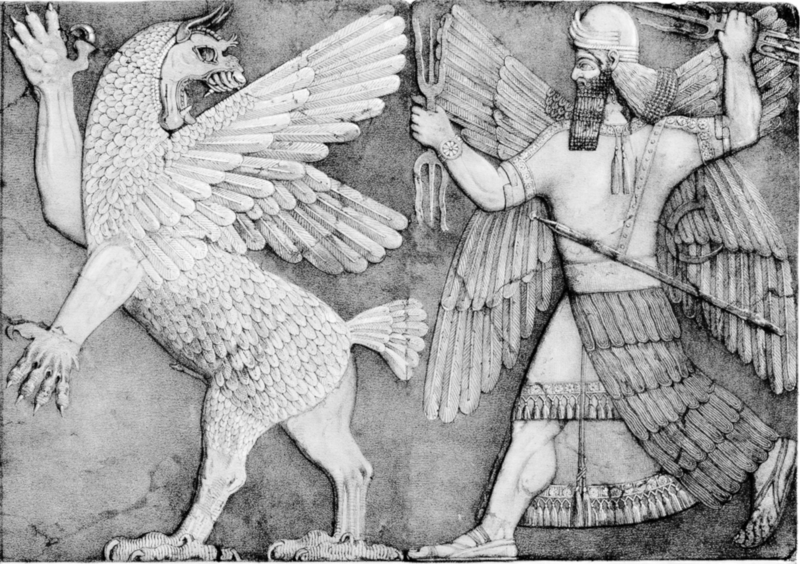

| With a heat dome baking most of the US this Midsummer, it seems relevant to honor a solar and heat deity, the Skythian goddess Tabiti or Tapati. Her more common name, Tabiti is the Greek version of the "Scythian *Tapatī, which meant "Burning One" or "Flaming One.” Among the Indo-Iranian descendants of the Scythians, she became the fire god Agni and the Persian concept of holy fire, Atar. The Skythians made no altars to their gods and left no written records; reconstruction of their religion is based on accounts from Greek historians and by comparing the archeological record to closely related Indo-Iranian cultures. |

Tabiti was the primary god of the Scythians. She embodied “primordial fire which existed before the creation of the universe and was the basic essence and the source of all creation, and from her were born Api (Earth Mother) and Papaios (Sky Father).” Tabiti “ruled over a pantheon of seven gods, …This heptatheism was a typical feature of Indo-Iranic religions.”

| According to mythologist Patrica Monaghan, Tabiti was a protective goddess, and her worshippers “sacrificed to her any who strayed into their territory.” She also held sacred oaths among the Scythians. The Ossetians in the Greater Caucasus Mountains, descendants of the Skythians, still honor Tabiti’s sacred fire by swearing their oaths on the hearth chains used to hold cauldrons over the flames. “As a goddess of the hearth, Tabiti was the patron of society, the state and families who protected the family and the clan.” |

Tabiti was associated with a solar calendar, illustrating her role in creating and ordering the universe.

In the fictional mythology of my novel Sky God’s Warrior, she’s named Tabati, and gives rise to colorful curses by the main character, Ayda, (who was fostered among Scythians) such as, "Tabati's flaming toes!"

In the fictional mythology of my novel Sky God’s Warrior, she’s named Tabati, and gives rise to colorful curses by the main character, Ayda, (who was fostered among Scythians) such as, "Tabati's flaming toes!"

RSS Feed

RSS Feed